MAPS OF THE BODY

The Ocean Depths explored by artist Isis Olivier in her Cartes du Corps

Written by Charles Wiseman

There is something visceral in the art of Isis Olivier. Coming from a celebrated family she has gone out of her way to be abstemious and avoid the trappings of fame. When I met her in Edinburgh she was beginning her Medical studies with the intention of becoming a physican, but soon took an about turn to focus on Agriculture before venturing out to Africa. At Edinburgh University we were both members of 'Third World First', an eccentric club which invited guest speakers from Asia, Africa and South America to discuss economic and social injustices and the impact these had made on their lives.

So it was not entirely unexpected when I heard that she was going to Sudan, to Wad-Sherifey, to work with the refugees arriving there from the war in Tigray. It was the time of Band Aid and I recall just how handsome a figure Bob Geldof cut. Young men like Jeremy Weller and I wanted instantly to become as dashing and passionate in our ways. So with the help of Annie Findlay, sister to Jeremy's playmate Jean, we started Student Aid, raising funds for African famine victims, which to this day I believe the almanac still shows as existing at a certain universities.

I gained some insights in to the real lives she had encountered there and how many of these people had found hope in religious fervour when near death. She had questioned the sincerity of this and indeed the experience was perhaps a lot for a young woman to take on.

When I sent her a picture of a sheep from my phone on my brother's farm she knew the exact name "Wiltshire Horn" immediately. She had managed to also fit in a year as a shepherdess.

*Thinking of the recent new autobiography of her father Tarquin,"So Who Was Your Mother?" I am aware how inspiring and at the same time what a heavy responsibility it is to come from such a family.

I was impressed by Tarquin's chapter on meeting a future Prime Minister of Jamaica and making an impact on him with suggestions as to how to create full employment. When the man campaigned to improve employment prospects, taking on board suggestions, he was voted in. The other side of celebrity is the continuous struggle with gutting gossip. Sir Laurence Olivier's official biographer, Terry Coleman, had claimed Olivier was gay in 2005, on the basis of "some letters written by a drunk, out-of-work actor called Henry Coleman." Tarquin admits. "He falsified the story to increase sales. I tore this theory to shreds in my own memoir".

In Chapter Ten of Tarquin's book, "So Who Was Your Mother?", he refers to the work he started for the Commonwealth Development Corporation (CDC). He is clearly a hard worker, which may be where Isis has inherited her energetic stance from. She went to work for famine relief, despite having embarked on a degree in medicine at Edinburgh. Her father, incidentally, has a sobre view of Aid as evinced by his practical experience.

He writes of the CDC: "...it sounded superb, offering finance and management in projects of great variety; agriculture of every size and kind; industry, heavy and light; hotels, harbours, railways, airlines, mining and development banks. This was not aid, which I distrusted. This was business, supporting the disciplines of profit and loss, sound balance sheets, with eight years' grace when it came to the fructification needs for certain crops such as palm oil."

In comparison to our generation who looked on -alongside Bob Geldof - in horror at the famine ensuing in Sudan, Tarquin might of course come across as unemotional, perhaps unfeeling. But having read Bob's "Is that it?" after Live Aid, and meeting him afterwards, I know the market has to survive and that aid functions as a last resort, given that it can both humiliate the people and destroy the fabric of native economies. We felt tangible anger as young people -as did Isis, with whom I had been part of 'Third World First' - in a way that was understandable. But as Geldof also stated, it comes down to leaders to share resources and Tarquin himself has indeed enough experience of travelling all around the world: to Tanzania, Central America, even designing the currency notes for Fiji, where my mother grew up. So I find myself apprehensive about questioning his indepth knowledge about the fine balance between economic and humanitarian intentions.

Tarquin also immediately grasped our concerns when I met him outside Chelsea Theatre with our play about homelessness and the homeless people who had come to see it. I was feeling let down, at the time, by technicians who we had hired for the Preview of our new play and their broken promises of the latest technology to power our multimedia production. As we were standing outside the theatre, with a group of ten people from the Kensington and Chelsea homeless community, he huffed "They are the real reason for, and centre of, this play", realising intuitively how upset I was at the slipshod attitude being adopted by the technicians to make real the filmic components on which Isis's contribution depended. It was both frustrating and diverting. Our overriding goal being to help raise awareness of issues facing vulnerable women on the streets and to make a coherent statement that would work harmoniously with the beautifully performed scenes, which had been directed so meticulously by Laura Hymers.

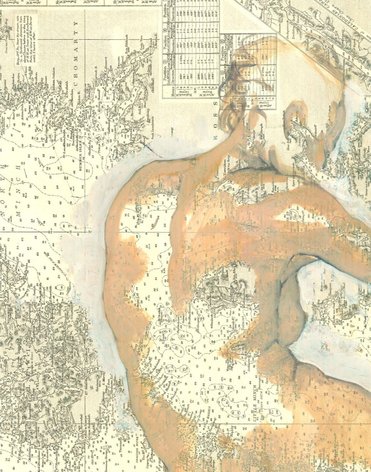

Actually I became aware that the high definition images she had sent me from her studio in the Cévennes, reminded me of the charcoal works of Käthe Kollwitz. Her The women's faces in these works, like in Isis's 'Three Graces' (above, featured in the performance), are sombre in burnt umber and writhing as though seeking to find themselves. There is a hint of Michelangelo's 'Slave', or 'Awakening Giant'. It is as if she is uncovering more in her own psyche the more she looks within. Just as Kollwitz paints of her own worries, in her 'mother with arms around child' series, so Isis's work - with her line drawings or the series 'Polish prisoners' - finds depths of feeling that move us effortlessly.

In Berlin, with its history of the Peace Movement going back to Brecht's invitation to Picasso - who went on to paint 'girl with dove' for the Iron Safety Curtain of the Berliner Ensemble - so Kollwitz's message rings out to all. Indeed Kollwitz Square, the cultural centre - where I lived when working at the People's Stage - was always a favourite for dissidents, in the days of socialism, who congregated and could talk without being overheard. Now the square is a major hub for young people and even has a playground for the children.

A family shows its real face in the influence and serious intent of its members. Sir Laurence, it recently emerged, worked during the War to influence top Americans into joining the efforts. And so it goes that philantrophy and humanitarianism are passed on reassuringly through the generations, despite the rebellions and determination of the young to carve their own paths.

More about Isis Olivier's work can be found at www.isisolivier.com

Ross, oil on paper, 40 x 30 cm, 2009, Isis Olivier

Three Graces, Isis Olivier

Nude, Charcoal, Isis Olivier

Copyright © 2013 Wand Arts Review www.thewand.org.uk. All rights reserved