DRAWN AS THE FISHES SWIM

by Marie Wiseman

Celebrated cartoonist and satirist David Low, made a career out of satirising the great political follies of his era and famously sent Hitler a scathing drawing of himself upon request signed "from one artist to another", but as Arnold Bennett once observed “Low draws as the fishes swim” and it was his skillful draughtsmanship that singled him out early in his career and allowed him to go on to become one of the leading political cartoonists of the 20th Century.

One of the most colourful and doggedly single-minded characters of the 20th Century, was first cousin to my maternal grandmother Norah Blanche Louise Baker. Jane Caroline Flanagan, David Low’s mother was sister to six siblings including Norah’s father Edward Flanagan, my great-grandfather who went to live in Fiji from New Zealand and later changed his name to Baker.

Low's mother, Carry, married a Scottish chemist from Dundee called David Brown Low, and they raised their family of eight in Dunedin until 1901, when aged ten, David and family moved to Christchurch where his father purchased a farm after winning a lottery and went on to compound cure-all patent medicines.

By the time of the move to Christchurch, his formal education considered over by his unorthodox parents, David proceeded to bone up on classic literature in his own education programme, from the heights of trees in the apple orchards of the farm, and converted an old chicken house into a retreat for practising his precocious drawing skills, by copying the English comics he avidly collected , such as Chips, Comic Cuts, Larks, and Ally Sloper’s Half Holiday. Later in life, in his autobiography, Low seems to own that his confidence and persistence might be traced to his father's unconventional approach to raising his family. Being taken with his siblings to the racecourse and shown how to bet intelligently, with the aid of Turf Register and Handbook of Form, is one development that must surely have chiselled a lasting impression on his personal future parameters.

He soon began entering drawing competitions and it was not long before he was collecting prizes and approaching newspapers with his first cartoons. His first on public affairs, was published in the Christchurch satirical weekly, The Spectator, at the age of 11, when he was then commissioned by that publication to illustrate two jokes each week. So successful did he become, that newspapers in both New Zealand and Australia were quickly seeking his work. He even contributed police-court drawings to New Zealand Truth! At the age of 17 he had secured the post of full-time Political Cartoonist for a Christchurch weekly, and some three years later, employment on the staff of the Sydney Bulletin (1911), though working mainly from Melbourne by then. Studies he had undertaken at business college in New Zealand had taken second place, when for a time he had also enrolled at the Canterbury School of Art. However, like many artists, he had found the emphasis on technique stultifying, and left to begin a brief stint with the Canterbury Times. Here he objected, as he would throughout his career, to being dragooned into drawing promotional cartoons, this time to promote compulsory military training.

By the beginning of the great War, at the age of 23 in Melbourne, he was turning out cartoons vehemently opposed to Australian Prime Minister William Morris Hughes, especially over the issue of conscription. The Billy Book, lampooning Hughes, drew praise from Arnold Bennett who observed: “Low draws as the fishes swim”. Though there were personal clashes as a result, it was in the end through this sometime acrimonious link, that David Low moved on in 1916 to London’s Fleet Street and the start of his meteoric career in England, eventually joining the London Star for the handsome salary of 3000 pounds a year, though not before he had won a long battle for the guarantee of freedom from editorial constraint, nearly three years later.

Before leaving New Zealand, he had met and known for just three days, a lady called Madeline Kenning. From London he telegraphed a proposal of marriage, with prepayment for a single word response. Her positive answer was the beginning of a lifetime happy union that lasted until his death in 1963.

Almost since the time of Hogarth, people had seldom been so scandalized as they were by Low’s ridicule of public figures. One of his cartoons of the time, depicted Lloyd George astride a two-headed ass, intended to represent the Tory-Liberal coalition government of the day. His response to the Prime Minister’s anger at the conception of this monster, was to say: “It didn’t have to be invented!”

In time he came to the attention of Lord Beaverbrook, the newspaper baron, who tried to win Low to his own newspaper, the Evening Standard. Once more this caricaturist, always a political radical and a law unto himself, held off for three years, until his demands for absolute independence from any constraints were met, before he joined that newspaper in 1927, at a salary of 7000 pounds a year. In later years Low was earning a salary in the region of five figures and in time, after his cartoons had been syndicated to some 220 newspapers worldwide and his reputation had achieved international acclaim, his earnings became stratospheric for the time.

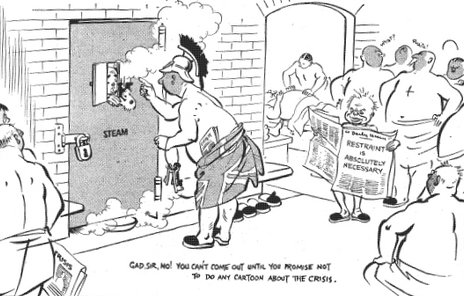

Low remained for some 22 years with Beaverbrook’s London Evening Standard. During this time of dogged independence in the face of opposition, his cartoons often included attacks on Beaverbrook himself, whom he once depicted as a witch on a broomstick, preaching “politics for children’s minds”. On another occasion he portrayed the press baron about to throw a giant spanner into the works of the British war machine. Beaverbrook’s response to the conundrum of why he did not sack his cartoonist, was to say: “I have, often, but he won’t go”. However, in truth, Beaverbrook was only too aware that the very keystone of Low’s success, was his liberty to attack as he pleased, whatever he deemed political crassness and downright evil. There were times when his satire was quite openly at odds with Beaverbrook’s editorials; his cartoons foretelling the rise of fascism, often even printed on the same page as the paper’s conservative editorials. In one depiction, the character of Colonel Blimp, one of Low’s inventions from 1934, is seen, Evening Standard in hand, remarking: “Gad Sir, Lord Beaverbrook says we ought to save the Empire, even if we strangle her in the attempt”.

As an internationally celebrated cartoonist, and relentless critic, his mordant depictions of characters like Mussolini, Franco and Hitler were widely seen, including in Italy and Germany. In particular, Low's rendering of Hitler's defining forelock and toothbrush moustache made a profound impact and in time the cartoons were banned in both countries and Low put onto Hitler’s Gestapo blacklist - for the Reich's planned occupation of Britain. His response to Beaverbrook’s order to underplay Mussolini’s attack on Abyssinia, was to depict three monkeys in the likeness of his boss with the caption: “See no Abyssinia, Hear no Abyssinia, Speak no Abyssinia”. In May 1935, a cartoon ridiculing Mussolini's ambitions in Abyssinia led to a ban on the Evening Standard and Manchester Guardian in Italy. Winston Churchill famously quipped about Low, after he himself was the butt of one of Low's cartoons (despite their common singular admonishments against the twin evils of appeasement and proposed disarmament ): "You can’t bridle the wild ass of the desert, still less prohibit its natural heehaw”. He also called him “a green-eyed young Antipodean radical” and tried to ban a film based on the character Colonel Blimp!

Not all victims were so unwilling, however, as to excommunicate Low. J.H. Thomas, the Socialist leader, portrayed by Low as “Rt. Hon. Dress Suit”, remained on friendly terms, as did the British Home Secretary of the mid-1920’s Joynson-Hicks, who sent Christmas gifts of cigars each year, “from your most loyal victim”. Beaverbrook himself was probably the most long-suffering, though of course had most to gain from his forbearance.

Most famous of the Low inventions were the TUC Carthorse, the Coalition Ass, Musso the Pup and Colonel Blimp, whose character has passed into the English language as the epitome of bumbling, muddle-headed conservatism: a plump bald-headed figure with a walrus moustache, decked out in a plethora of decorations from ancient wars, spouting platitudinous and preposterous commentary on the politics of the day, such as: “Gad Sir, Churchill made an irrevocable decision to be guided by circumstances with a firm hand”. Low insisted that his Blimp was genuine and that he had overheard him in a Turkish bath, dressed in the altogether, pronouncing that what Japan did was no concern of Britain’s!

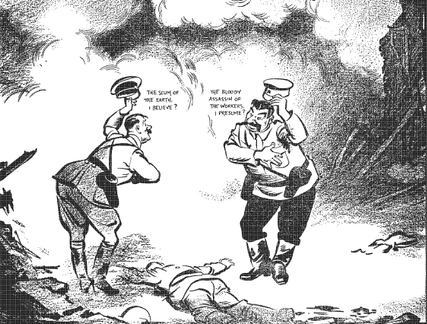

Both Low and the Evening Standard were publicly rebuked by Stanley Baldwin and his successor Neville Chamberlain, for publishing denunciations of the Nazi dictators and their appeasers in the English political arena of the 1930’s. Low’s defence was to say: “ I see most of the leaders of the world as little men. Rather ridiculous men at times, trying to grapple with causes and movements that are too big for them. ….. I try to show them to the world as little men. And when I think they deserve it, I kick them in the pants.” While the political analysts of the day were busy portraying Hitler as some enigmatic force to be reckoned with, Low was taking him at his word, viewing him as essentially simple-minded and "uncomplicated by pity", and often drawing prescient depictions of events to come. His most famous war-time drawing, described by Low as "the bitterest cartoon of (his) life", showed Hitler and Stalin viewing each other over the corpse of Poland in 1939.

The caption has Hitler addressing Stalin: "The scum of the Earth I believe?" and a smirking Stalin replying: "The bloody assassin of the workers, I presume?". Astonishingly, despite the fact that from 1923, with his early cartoons criticising the Versailles Treaty and the impossibe reparations imposed on the young German republic and warning of the need to support the Weimar government, and that he would ultimately be most famous for his unremittingly vociferous forewarnings of the ambitions of the Fuhrer, when asked to gift a few of his original works in the 1930's to Hitler, who professed interest in cartoons, Low allowed them to be despatched, "from one artist to another!"

In the early 1930's Low had immersed himself in the study of the comparative political ideologies of communism, fascism and Nazism. He was also to describe himself as the small boy who asked "why?", when he heard "God Save the King"!

From 1932, Low visited Russia, later travelling extensively in Europe, as well as North and South America, (his sister Dorothea was living in Bogota). His work during the war years was broadened by that terrible period and his patriotism was unquestionable. He regularly broadcast on the BBC Pacific Service and to the Far East during that time.

In his long career, Low drew for the New Statesman in the 1920’s and 30’s, two famous series of pencilled caricatures of politicians and literary figures, as well as for the Guardian and Daily Herald, in addition to what was undoubtedly his major output, for the Evening Standard. His drawings filled half a tabloid page, to dramatic effect. It is said that he was influenced more by Continental artists such as Daumier and Philipon, than English political cartoonists; dropping the pen for a flowing brush (made from his own hair!) and brandishing it with the ease of a Chinese master, albeit over the top of a worked and re-worked pencil sketch. Following the war’s end in 1945, he left the Beaverbrook empire and in 1950 joined first the Labour Daily Herald and later in 1952, the Manchester Guardian, where he remained for the rest of his life. He also contributed to Picture Post, Punch, Illustrated and Nash’s Magazine, amongst others.

From 1908, at just 17 years of age, with Low’s Annual, and throughout his long career, many publications were issued, most famous of which were probably Low’s Political Parade in 1936, Europe at War, Low’s War Cartoons, and the World at War in 1941, and Years of Wrath 1946. He continued with Low’s Cartoon History 1945-53, Low Visibility in 1953 and The Fearful Fifties in 1960.

He received two honorary doctorates in his lifetime and was finally knighted in 1962 at the age of 71, having declined this honour when it was first proposed in the 1930's. His prodigious output continued to the end of his life in September, 1963. In all, Low produced over 14,000 cartoons, syndicated worldwide to newspapers and magazines. Many of these are now collectors’ items.

Low's unequivocal voice and stance were surely gifts to the times in which he lived. No-one comes close in our own times to possessing the authority, insight or courage to compel the world's leaders, none of whom can any longer be called statesmen, to hold themselves accountable for the atrocities, perversions of truth and hubris which have for decades daily insulted the memory of those millions who gave their lives for the tenuous peace of our modern world.

A fan letter received by Low states 'A Jewish refugee from Vienna, a very old man, personally unknown to you, cannot resist the impulse to tell you how much he admires your glorious art and your inexorable, unfailing criticism'. The letter is signed "Sigmund Freud".

Copyright © 2013 Wand Arts Review www.thewand.org.uk. All rights reserved